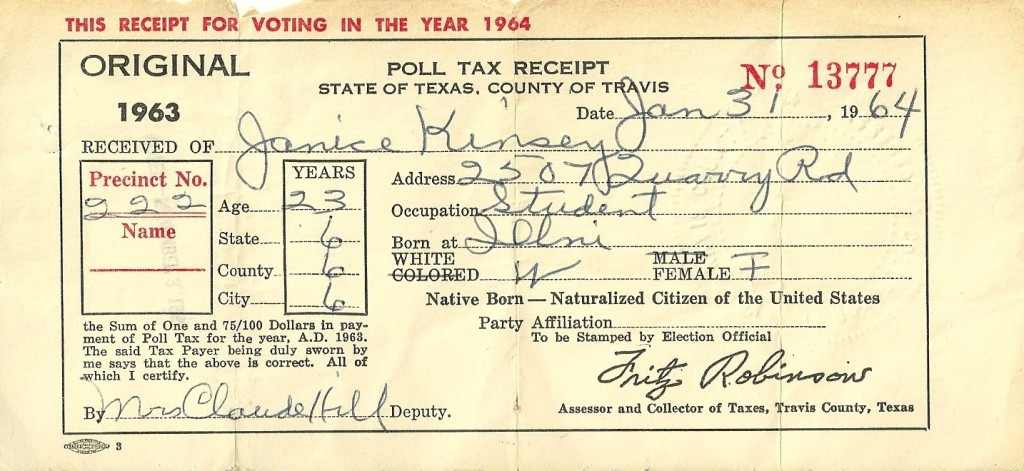

Image courtesy of Brian D. Newby

Would you like to contact your city council member? That will cost $5.00. Would you like to vote in the general election? That will cost you $15.00. Would you like to attend a public meeting? Admission is $25.00.

There are certain elements of our democratic system of government that are so essential to its freedoms and principles that we have to make them as accessible as possible and provide them free of charge. Voting is probably the most crucial example of this which is why the poll tax of the Jim Crow era was made unconstitutional in 1964 by the 24th Amendment. Unfortunately 1964 is not very long ago and there continue to be efforts to make essential acts like voting more and more difficult including a recently proposed tax penalty in North Carolina for parents who’s children would like to vote while they’re in college. Ironically, the states which have some of the best voting practices today, Washington and Oregon, do impose a small fee of $0.46 or whatever the cost of postage is, but you’d think with all the money saved by administering a whole election by mail they could include the postage. We have it easy though, folks in many countries can be fined for not voting.

I bring up the relatively recent injustice of the poll tax because I think there are some parallels with fees imposed to access public data. This topic has been given a fair amount of attention this year following the loss of Aaron Swartz and demands to make all publicly funded scientific research available to the public. Yet there are still many tough questions and the Knight News Challenge on Open Government has definitely helped stir up the debate even more. This has been discussed by Matt McDonald and more recently with David Eaves’ post questioning the business model behind the DemocracyMap Knight News Challenge proposal.

I know straw man arguments against liberating government data and leveraging civic technology are in vogue these days, but I expected a little more from David Eaves’ TechPresident story. As David points out, we’ve known each other for a while and respect each other’s work, but that’s partly why I was so taken aback by what he wrote.

David writes about DemocracyMap because it’s the most viewed proposal of the Knight News Challenge semi-finalists and he’s fearful of it lacking a business model or being so corrupted and destructive with grant money that it will kill other solutions he sees as more viable like Azavea’s Cicero. He later goes on to talk about other projects he’s more optimistic about. I too care deeply about the sustainability of DemocracyMap which is exactly why it’s one of the only proposals that includes a section specifically devoted to sustainability and why it makes several mentions of business models and strategies for the success of the project including intentional obsolescence. The News Challenge didn’t ask anyone to include details on sustainability or business models, but I thought it was important enough to include anyway. What’s so confusing about David discussing DemocracyMap with fear is that none of the projects he goes on to discuss say much of anything about how they will be sustainable or what their business model will be. Furthermore, they all ask for more funding than the DemocracyMap proposal calls for, so I’m not sure why it’s the example he uses of being corruptible by grant money.

The other part that’s confusing about the post is how he pits DemocracyMap against Azavea Cicero. If David had talked to me before writing this he would’ve learned that I’ve been in touch with Robert at Azavea for a long time and he’s been supportive of DemocracyMap. In fact, I was meeting with someone who Robert had introduced me to when David posted this piece. While I have great respect for Robert’s work and Azavea and plan to continue coordinating with him, what’s troubling about the way David characterizes Cicero is that he assumes it’s already solving the problem and he assumes that it has a sustainable business model which should be an indicator of success. If I believed all those things to be true, I probably would not be doing this project, but the truth is there’s still a long way to go to solve this problem.

Perhaps it’s because of the way Cicero is shown as a product for sale that led David to think it was already solving the problem better than DemocracyMap. Yet there’s a wealth of easily available public data that’s not even included in Cicero’s results such as basic city and county contact information published by the Census Government Integrated Directory. DemocracyMap doesn’t just aim to cover thousands more cities than Cicero, it already does. The same could be said in comparing DemocracyMap to VoteSmart or many of the other services that are called out in the proposal.

The other conclusion that David jumped to is that Cicero is already sustainable, but as I knew in talking to Robert privately and as he later made public in his comment, that’s not true either. Just because something has a for profit business model does not mean that it’s a sustainably viable solution. This is very much what I was eluding to in my proposal by emphasizing that I didn’t want to repeat the history of the efforts that had failed to make a business by charging for this data. Even more confusingly, David later left a comment claiming that my proposal never stated this, but it was there all along.

While David explicitly thinks it’s dangerous when “success can be seen as external from sustainability” I actually think it’s very important to think of them separately. They are certainly interrelated, but it’s helpful to think of them distinctly since it’s often counterproductive if they are too deeply intertwined. In fact, I would argue that this more nuanced way of thinking is also in play at Azavea which is why Cicero continued to operate even at a loss and why the company is a B Corporation. In fact, this distinction is often consciously recognized in the civic sector even for efforts which are good at bringing in revenue. I suspect this is also why Matt McDonald expressed his interest in establishing a B Corporation or why even business savvy outfits like TurboVote are set up as non-profits. This isn’t to say that sustainability or profitability are bad, quite the contrary, but it is important to recognize that it doesn’t equate to successfully solving your problem. In fact, too much of a blind drive toward profit, can actually make it harder to be successful. We even see this with big for-profit companies where too much focus on short term gains can hamper long term profitability. Increasingly, even musicians and writers are finding that if they make their work more easily available, even freely available, they’re more likely to be successful and even more profitable in the long run. Traditionally, news publications have tended to lose money on the best investigative reporting they do, and we definitely need to keep working on creative ways to support that, but simply basing success on the profit of each and every story is not a recipe for good journalism or a good company.

In the context of democracy you might also consider that the folks in the US who see the market as the tool to fix every problem and the only true indicator of success are often the same kinds of folks who are making it harder for people to engage in democratic processes resorting to even, you guessed it, economic pressure like new taxes to make it harder for people to vote.

This isn’t to say that David doesn’t recognize the folly of overwhelming financial influence. In fact he clearly states, “The key problem with money – particularly grant money – is that it can distort a problem and create the wrong incentives.” which makes it all the more confusing why he also argues for a such a simplistic profit driven approach for public access to public data. To be fair, in this case he’s concerned by the threat of unseating an incumbent and the risk of destroying the whole market by not being a sustainable replacement. To his credit, and as Robert later elaborates, this is a totally lucid point. In the private sector, profit driven ventures tend to condone more risk because they often care more about the possibility of turning profit than the chances of hurting their whole industry. Social entrepreneurs and grant makers on the other hand have to be much more discerning and have a broader understanding of their field if they genuinely care more about solving the problem than turning a profit. However, in this scenario this isn’t a particularly valid concern since the incumbent he cites or any of the others I cite in my proposal are not particularly sustainable nor fully solving the problem. If David had done a little research, this would’ve been obvious. Furthermore, if this kind of concern isn’t thought out more carefully it has the potential of being even more counterproductive by simply maintaining the status quo rather than striving for progress.

I had to re-read David’s use of the word “disruption” a few times because I’m so accustomed to seeing it used in a positive light, particularly in the context of new technology. The Code for America Accelerator runs under the banner of “Disruption as a Public Service” and Emer Coleman, the former Deputy Director of Digital Engagement for the UK’s Government Digital Service, has a new company called Disruption Ltd. While it’s true that there are some rare instances where a new company or project can be so destructive that it ruins the whole field including itself, the public sector is littered with stagnant, inefficient, unproductive systems that are in much need of disruption. In this context, the traditional “sustainability” of current offerings is often counterproductive – which is also why efforts like Procure.io are so important. As new software becomes cheaper and easier to develop, it becomes easier to see how many companies that profit from government inefficiencies are actually stymying progress. As was mentioned earlier, “money can distort a problem and create the wrong incentives.” The lobbying efforts of Intuit and H&R block against “return-free filing” are a potent reminder of this and if you need a refresher on the crippling consequences of money on the broader workings of a democracy, I encourage you to see Lawrence Lessig’s latest talk to remind yourself how much work still needs to be done.

The trick is to position the incentives associated with sustainability in a way that provides the most leverage toward progress and the common good. The smartest and most successful companies tend to put their profit driven incentives at a place that forces them to make the most progress and deliver the best products and services in a way that advances their whole industry. Often this means disrupting the status quo and sometimes you are the status quo and you have to cannibalize your own company to move forward. Even Apple’s advancements with the iPad killed their own laptop sales, but it helped advance technology for everyone and ultimately delivered higher sales for Apple.

In the case of charging for access to public data, it’s not only ethically questionable, but it’s counter productive and usually unsustainable. The most common ethical quandary in charging for public data is that you are making people pay for data their tax dollars already paid for. In the case of DemocracyMap we’re also talking about obstructing access to some of the most essential information needed for us to interact with our own democracy and essential government services – hence the reference to the poll tax earlier. When these kinds of sensitive ethical issues are less applicable to a particular dataset, I can understand the approach of companies that initially bootstrap themselves by selling access to data. I think Brightscope is a common example of this. However, I think it’s risky and unsustainable to build a business on access to the data alone. For one thing, scraping public data rarely involves much ingenuity or creativity, it’s usually more of a brute force thing. This means your competitors rarely have much of a barrier to entry. For another thing, the real value of data to the people who actually need it is typically not realized until it’s meaningfully analyzed or given enough context to be relevant to them. The final point is that governments increasingly understand the value of opening their data and have the potential to undercut you with free access.

Data is not a zero sum resource like a parking spot, it’s value tends to increase when more people have access to it. This is true even in the sense of delivering more revenue to those who provide the data. For example, making public transit data freely available can increase ridership and improve support for public funding, both of which can increase revenue to the transit agency. Governments are learning this and starting to make their data open by default. You don’t want your whole business to be threatened by a simple policy change that’s becoming increasingly common. Furthermore, under US law, the facts that comprise most raw public data are not subject to copyright, so selling or licensing this data is dubious anyway. Again, the best and smartest companies are the ones who are always aware of these threats and advance themselves preemptively.

I would argue that the most stable and progressive way to position sustainability in the context of public data is at the extremes: the point where the data is produced and the point where it’s analyzed and contextualized, not with a pay wall at the point where it’s published. In the case of DemocracyMap, I think it’s important to focus on the root of the problem and work to ensure that this data is managed and published at the source in the most accessible and useful way possible. While DemocracyMap already provides basic tools to contextualize the data and will likely develop even more advanced ones, the main intent is to help ensure the conditions for an ecosystem where everyone can help play that role, particularly journalists and civic hackers. In some ways this may take the form of providing support and software as a service to cities, states, and other entities who manage this data internally, but in other ways it may even be about convincing those who can set policy at a high level. Over twenty years ago, back in 1992, the US Census did actually collect and manage a significant portion of this data, but they haven’t since. As the Census becomes more and more digital, I would love to see them better incorporate the goals of DemocracyMap. One of the most scalable ways to make this data more accessible is by establishing open standards much like I’ve done with Open311 and that is definitely emphasized in the proposal. So while I think DemocracyMap can help deliver revenue generating tools that are used to produce and maintain this data, one of the central goals is to make the current practice of scraping and manually aggregating data obsolete.

I do think that sustainably minded efforts tend to deliver the best results, but it’s also important to consider that some efforts are best served when they are made obsolete. It’s also worth noting how much leverage an investment in a few engineers can have even when there’s no revenue model whatsoever. The Voting Information Project has made a huge impact with just a handful of engineers and an investment that I’m sure pales in comparison to the money flowing toward the dozens of voter suppression laws that have been introduced this year. Carl Malamud deserves recognition here as well. If he had simply turned access to EDGAR into a business of his own back in 1994 rather than making it freely available and ultimately getting the SEC to do so themselves, then we might not even have the momentum behind liberating government data that we have today. Carl continues to have a big impact with this strategy, now primarily focusing on liberating access to legal documents such as the legal code for the District of Columbia. The D.C. Code, the law which governs D.C. just like many other municipal codes, is one which you traditionally had to pay for to get a copy. Normally this was sold for over $800, but after Carl made it freely available online the District government was compelled to do so as well. Charging for this is particularly egregious because it’s not like most data which is the byproduct of some government operation or policy, it is the law itself and multiple court cases have already made it clear that the law must be freely available. In the grand scheme of things I don’t think it costs a whole lot to support the kind of work Carl and the VIP are doing and i think these catalysts are well worth the investment to ensure that people don’t have to pay extra for civic education and civic engagement.